Home

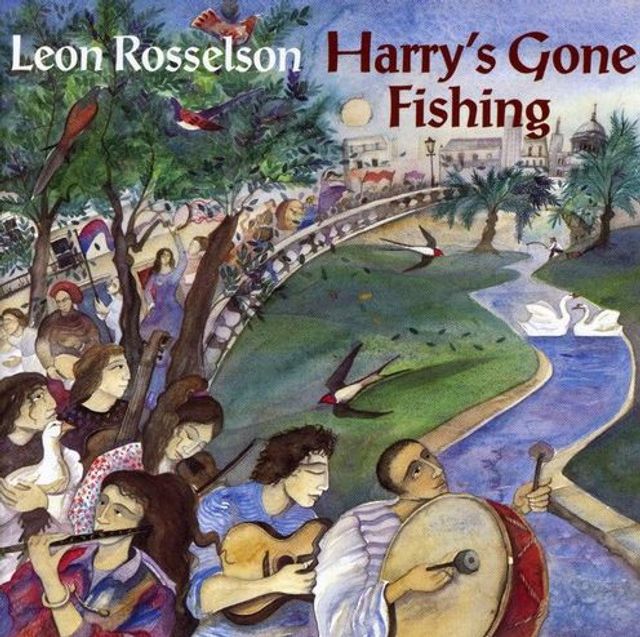

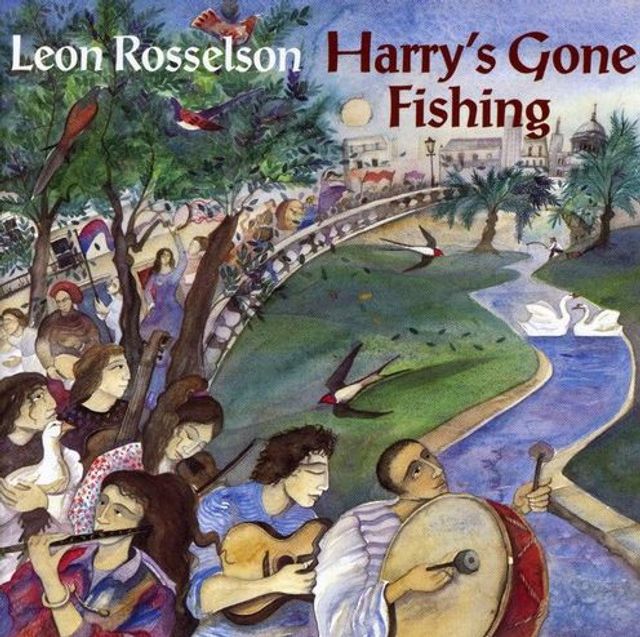

Harry's Gone Fishing

Barnes and Noble

Harry's Gone Fishing

Current price: $16.99

Barnes and Noble

Harry's Gone Fishing

Current price: $16.99

Size: OS

Loading Inventory...

*Product information may vary - to confirm product availability, pricing, shipping and return information please contact Barnes and Noble

Leon Rosselson

begins and ends his first album in quite a while with personal statements.

"It's Just the Song"

is an explanation of why he writes and sings songs, not to achieve social change, not for personal aggrandizement, not even for critical and popular approbation, but just for the sake of doing it: "The song's the thing." In

"Encore,"

he acknowledges that "I've been writing songs for over 35 years but I don't seem to have got very far," yet he thanks his listeners for listening all these years. Both songs are typical of

Rosselson

; they are verbose, self-indulgent, self-centered, and self-righteous yet always engaging and entertaining. He comes off like an obsessed know-it-all, the sort who talks for 95 percent of every conversation he's in, freely mixing broad, firmly held political beliefs with personal details. He's fascinating, probably right most of the time, and more than a little nutty. He speak-sings in a calm, well-articulated English accent, his writing full of British terms and outright slang that will sometimes confuse American listeners. But his point of view is clear: He's a doctrinaire British socialist, devoting the title song to his opposition to gentrification, opposing money itself in

"Money Matters,"

and reissuing

"You Noble Diggers All (The Diggers' Song)"

from his 1979

If I Knew Who the Enemy Was

album, a musical setting of the call-to-arms by the 17th century proto-Communist Diggers leader

Gerrard Winstanley

. Americans may find such sentiments less easy to stomach when they are more current and closer to home. In

"Postcards From Cuba,"

visits one of the last bastions of Communism on holiday and comes away with a series of disconnected impressions that don't seem to justify his final verse, a rousing tribute to the country as a left-wing symbol. And in

"Child Killers,"

one of two songs in which he writes from inside the mind of a murderer, he analogizes the Columbine tragedy to U.S. foreign policy. "Am I being presumptuous" in making such a connection, he asks in a sleeve note. Most would say yes. Still, it's hard to dislike

as his words come out in torrents, overwhelming the modest musical accompaniment. His repeated hope for a "world turned upside down," not coincidentally the title of one of his best-known songs, is infectious, even if the world he envisions is so clearly a fantasy, even to him. ~ William Ruhlmann

begins and ends his first album in quite a while with personal statements.

"It's Just the Song"

is an explanation of why he writes and sings songs, not to achieve social change, not for personal aggrandizement, not even for critical and popular approbation, but just for the sake of doing it: "The song's the thing." In

"Encore,"

he acknowledges that "I've been writing songs for over 35 years but I don't seem to have got very far," yet he thanks his listeners for listening all these years. Both songs are typical of

Rosselson

; they are verbose, self-indulgent, self-centered, and self-righteous yet always engaging and entertaining. He comes off like an obsessed know-it-all, the sort who talks for 95 percent of every conversation he's in, freely mixing broad, firmly held political beliefs with personal details. He's fascinating, probably right most of the time, and more than a little nutty. He speak-sings in a calm, well-articulated English accent, his writing full of British terms and outright slang that will sometimes confuse American listeners. But his point of view is clear: He's a doctrinaire British socialist, devoting the title song to his opposition to gentrification, opposing money itself in

"Money Matters,"

and reissuing

"You Noble Diggers All (The Diggers' Song)"

from his 1979

If I Knew Who the Enemy Was

album, a musical setting of the call-to-arms by the 17th century proto-Communist Diggers leader

Gerrard Winstanley

. Americans may find such sentiments less easy to stomach when they are more current and closer to home. In

"Postcards From Cuba,"

visits one of the last bastions of Communism on holiday and comes away with a series of disconnected impressions that don't seem to justify his final verse, a rousing tribute to the country as a left-wing symbol. And in

"Child Killers,"

one of two songs in which he writes from inside the mind of a murderer, he analogizes the Columbine tragedy to U.S. foreign policy. "Am I being presumptuous" in making such a connection, he asks in a sleeve note. Most would say yes. Still, it's hard to dislike

as his words come out in torrents, overwhelming the modest musical accompaniment. His repeated hope for a "world turned upside down," not coincidentally the title of one of his best-known songs, is infectious, even if the world he envisions is so clearly a fantasy, even to him. ~ William Ruhlmann